Scientific writing can be a daunting process, but the impact can be great. This is one of the primary ways to communicate your research findings with the wider scientific community and establish your research profile.

In this blog post, we will explore the goals of scientific writing whether this is for a journal paper, an MSc dissertation or even for a PhD thesis. We will investigate the anatomy and the typical structure and break down the main parts. This guide acts as a framework when you need to communicate your research contributions, experimental studies, or the new tools and models you have built. You can also download a template to help you structure your thesis.

Keywords: scientific writing, journal paper structure, writing tips, MSc dissertation, PhD thesis

Setting the scene

The goal of a scientific paper or thesis is to communicate new knowledge, identify and solve a problem that our community is tackling with. The problem to be solved, or the new knowledge usually conforms with the following 3 dimensions:

- Novelty: It’s a new problem that no-one solved before, or invent and a evaluate a new method, tool, or even identify a gap in the existing bank of knowledge. The keyword here is ‘new’, what new piece of information are you adding with your thesis or paper?

- Importance: How important is this problem you will be solving? What will be the impact of your solution? Is it worth the time and effort you will invest to solve it?

- Non-trivial: The complexity of the problem should relate with the length of your project. How complex is the problem?

Story telling

In scientific writing we communicate ideas, prove theorems, implement new models, and evaluate findings. We use objective language and tone by presenting information without personal bias or emotional language. We avoid journal style writing and sharing unnecessary information, do you really need to know that I woke up and after having a nice cup of coffee I run my experiments?

Form a story based on facts and findings and avoid giving peripheral details that are not directly relevant to the approach you followed to run your study or your findings.

Typical structure

In the following sections we will disect the typical structure of a scientific piece and understand the contents of each. In the next sections you can find writing tips and links to tempkates and external sources. Adapt and expand accordingly to fit your project.

Scientific papers typically begin with an abstract, followed by introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion.

Different domains might follow a slightly different structure, always check the submission guidelines of the journal, or conference you will be submitting, or the university guidelines for MSc or PhD submissions.

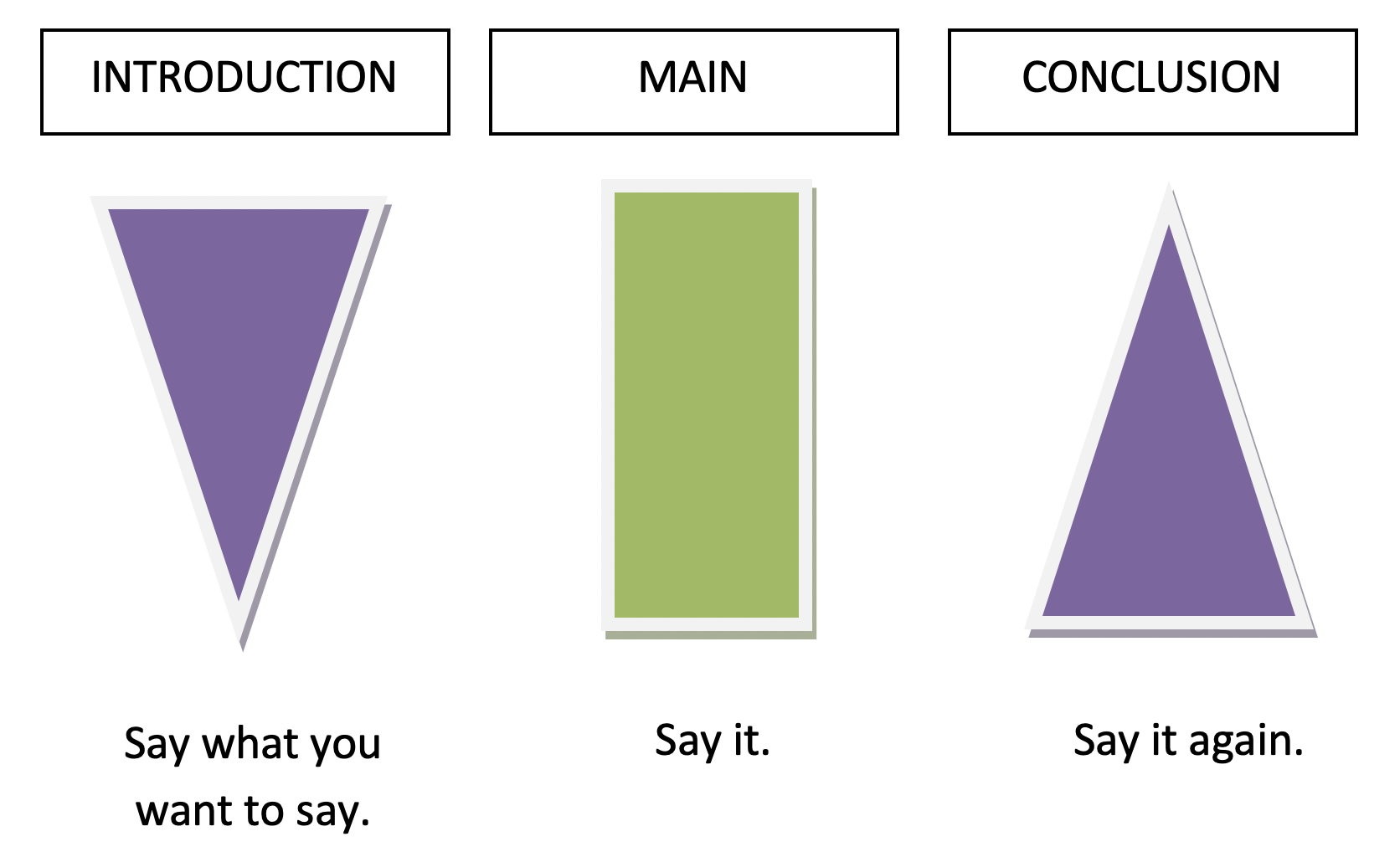

The triangles structure

I first found out about the power of triangles when I was writing my PhD thesis. Imagine that your entire project or study can fit within a rectangle. At the top of the rectangle you introduce the topic, define the problem, set aim and objectives, then towards the middle part you describe the methods you will follow to solve the problem and towards the lower section of the rectangle you present your results and position your findings.

The introduction of your thesis of paper will cover the entire story of your project focusing on the problem to be solved. The introduction will only provide a bried overview of the potential solution. The conclusion (or in journal papers the discussion section) will begin by reminding the readers what the problem was and focus more on the solution, or findings. The conclusion always mirrors the introduction - did you solve the problem that you originally said you would?

Abstract

We don’t usually judge a book by its cover, but we most definetely judge a paper by its abstract (and conclusion). The abstract is the very first thing that your readers will read. It’s a miniature of the entire paper. It sets the scene, defines the problem, describes the method taken, presents results and finally positions findings in the wider context - all of these in a few hundred words. You can structure your abstract to have the following sections:

- Background

- Methods

- Results

- Conclusions

The majority of journals have a word limit for the abstract.

Keywords

A set of words that describe your paper. What keywords would you type in google to find your paper?

Introduction

Introduction sets the scene and defines the problem you will be solving. Remember the problem needs to be non-trivial, important, and novel.

- Set the scene

- Explain what the problem is, and motivation (why is it an important problem?)

- Describe your project or study aim, objectives and hypothesis

- Very brief overview of potential solution or findings and the impact it will have

Forming project aims and objectives

Aim and objectives are two terms that are often used in the same way. In scientific writing though each has an important role to play. Aims are statements of intent and they are usually written in broad terms. They set out what we hope to achieve at the end of the project. Objectives, on the other hand, summarise the course of action (the approach, methods and steps) we will follow to achieve our aim. Difference between research aims and objectives:

- Aim = what you hope to achieve.

- Objectives = the actions you will take in order to achieve the aim.

When writing objectives, we typically use strong positive statements and verbs:

- Strong verbs - collect data, construct a model, classify, develop a method, devise, measure complexity, produce, revise feasibility, select, synthesise an analysis

- Weak verbs - appreciate, consider, enquire, learn, know, understand, be aware of, appreciate, listen, perceive

You can also use the SMART model to define specific and measurable objectives when writing a grant proposal, defining new tools, or capturing user requirements.

- Specific - be precise about what you are going to do

- Measurable – how will you know that you have reached your goal

- Achievable - Don’t attempt too much - a less ambitious but completed objective is better than an over-ambitious one that you cannot possible achieve.

- Realistic - do you have the necessary resources to achieve the objective - time, money, skills, etc.

- Time constrained - determine when each stage needs to be completed. Is there time in your schedule to allow for unexpected delays.

Background

You might need a background section to cover any background information to help your reader/examiner better understand the scene and context of your project. This could be very short and included in the introduction section and cover known facts that will help establish the context of your project - use citations.

Literature Review

This section should answer the question: ‘What did other people do to solve the problem (or a similar problem) you are solving?’. This should reflect your hypothesis (or aim) and highlight any gaps in the literature that your project will fill in.

- Start by defining the question(s) you will be answering,

- Break it down into sections,

- Identify relevant papers

- Critically evaluate the contributions/methods of each paper

- Draw conclusions

- Finally, summarise your findings to answer the question(s) and derive next steps/goals for your project, i.e. how will you apply your findings from reviewing the literature?

If you are conducting a systematic literature review, you can follow the PRISMA guidelines to help you structure your process and presentation of results. More info here.

Methods and design

Explain the approach/process/method/models/tools your will use in a way that your readers can potentially replicate your methods. Also describe the design of your study i.e. how many participants, their backgrounds, your methods for capturing and processing data, datasets used to train your model, etc. You can use a diagram to summarise and illustrate the process you followed.

Results

State the results of your implementation of the method. Provide figures/tables/charts provide minimal explanation. Interpretation of your results will be in the next section.

Discussion

Explain your results and position them in the wider context. Compare your findings with other papers in the literature. Include limitations and future work that might be needed.

Conclusion

A very brief section (few paragraphs) to summarise key findings and answer your original question/hypothesis.

References

Check the submission guidelines on which referencing style you should follow.

Appendix (for PhD and MSc dissertations)

Add any screenshots or figures/tables/charts that are not vital for your project/results but complement it. For example, ethics approvals, questionnaires, etc.

Tips for writing

Phrasebank

Feeling stuck, and don’t know how to start? The University of Manchester Library published a phrasebank to help you phrase your ideas and write them down. Simply browse through the menu on the left and pick the type of phrase you are looking for. This is not the only phrasebank out there.

Feedback

A new pair of eyes is always helpful when you are too invested in the project (well it’s your project and u should be) to make sure that the key contributions and messages are clear to an external audience who might not know the details. Also, when we reach version 5.6.7_final_comments_reallyfinal of the document, it’s easy to miss mistakes. Use a tool or ask a friend to read through it (promising a drink increases your chances).

Don’t aim for perfection

Writing is really an iterative process. Perfection doesn’t really exist. Start small, break it down into parts, and start tackling a step at a time. We iterate through our writing drafts, and improve them.

Read before you write

Find similar papers and identify the structure, language and tone they use to explain complex concepts. You can laso use diagrams, charts and tables to form and convey your story.

Ethical considerations

Ethical considerations are important in scientific writing, including proper attribution of sources, accurate reporting of data, acquisition of appropriate ethical permissions, ethical collection and handling of data and disclosure of conflicts of interest.

Feeling stuck?

Turn off your critical self-concious by putting some music on, or go to the quiet place in the library, or even use a different colour font (I use grey colour). You can only find what works for you by trying out different strategies.

Download template

You can download a word doc template to help you structure your journal paper, thesis or dissertation.

Versions

| Version | Date | Updates |

|---|---|---|

| V1.1 | June 2023 | Template created. |